Washington Post Op-Ed

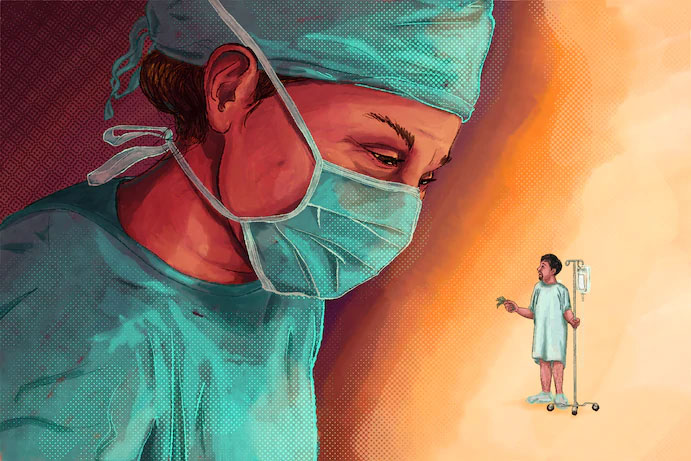

The health-care industry is letting surgeons behave like muggers

Cynthia Weber Cascio is a principal at M&C Media and a former CBS News correspondent.

We’ve been hearing a lot about surprising medical bills lately — horrible stories about wages being garnished because of large unpaid bills, people losing their homes, even people taking their own lives because of medical debt.

Yet the public still seems largely unaware that such horrendous situations could happen to anyone — even those with great health-care plans. That’s because our health-care system is ripe for bad actors to abuse patients in emergency situations. I should know; it happened to me.

About a year ago, I began to have stomach discomfort and thought I had overdone it at Starbucks. The pain got worse overnight. Antacids didn’t help. Then came the nausea, 102-degree fever and pain that had moved to my lower right side, making it difficult to lift my leg. By dawn, I knew it was appendicitis and told my husband we had to go to the hospital.

There were several options, but I felt so sick that we chose a nearby hospital, which we have long trusted for our family’s health. A CT scan and bloodwork quickly confirmed acute appendicitis. I would need surgery immediately. Not to worry, the ER doctor told me. They had a good surgeon on call. Things were moving efficiently and smoothly. We were impressed.

Then we met the surgeon as I was being prepared to be taken into the operating room. He explained that if he didn’t operate right away, I might get sepsis and die. He also said he didn’t take my insurance but assured us I was in capable hands, as he was very experienced. After asking about our occupations, he announced his fee for my laparoscopic appendectomy would be $15,000. We were stunned by the timing and the amount. Was this supposed to be a negotiation?

But there was no time for discussion. I was wheeled off for a straightforward surgery that took about 35 minutes — not much longer than a colonoscopy. The procedure went well.

Eventually, the surgeon’s bill arrived: $17,000 including charges for an ER consult neither my husband nor I recall. I called the insurance company (for which we’re paying more than $25,000 in annual premiums). Sorry, he’s not one of ours. No contract with us.

Fortunately, my insurance covered all other related hospital costs — the ER doctors and tests, the operating room, medications, the anesthesiologist’s fee — but that still left us with the $17,000 charge from the surgeon. That’s more than seven times the out-of-network, uninsured rate for the hospital’s locale, according to FAIRHealth Consumer.

I appealed to the Maryland Insurance Administration, which regulates the state’s insurance industry. MIA was sympathetic, but there was nothing to be done because the surgeon didn’t have a contract with the insurance company.

I wrote to the head of the hospital and patient relations. Surely the surgeon mistakenly added an extra zero? Was the hospital aware business affairs were taking place in pre-op? Can an out-of-network surgeon simply make up any fee on the spot? I felt violated.

Three months later, I got what appeared to be a computer-generated email survey asking if I had any complications. It also said the surgeon who performed my procedure was part of a quality control panel. I have heard from the hospital subsequently — in the form of more general emails, asking me to donate money.

Meanwhile, we appealed our insurance company’s refusal to cover the surgery, and as we waited for its final determination, the surgeon kept asking the status of the claim. In an email exchange, he offered to reduce his fee by 30 percent if it would help.

Finally, I went to the Maryland attorney general’s office, which wrote a letter to the hospital. With that, we came to a resolution: I agreed to pay the surgeon what I felt reasonable — $3,000 — generously above the customary rate for an uncomplicated laparoscopic appendectomy in our area ($2,330).

I asked a relative, an esteemed big-city surgeon, why this happened. Many doctors and hospitals are squeezed, he said. Some doctors work in public hospitals by day, privately at night. Care for an uninsured burn victim, for example, can cost millions. Everything is a balance — judgment, ethics, conscious, subconscious. Which is why massive overhaul is needed.

But reform appears in no one’s best interest, especially given the current political climate. Insurance companies, hospitals and doctors are businesses. Lawmakers, even at the local level, often serve on hospital boards and in some cases are major donors.

Telling a patient to negotiate a bill directly with the provider, as my insurance company suggested, is akin to telling the victim of a mugging to ask the thief for their purse back. It’s uncomfortable and intimidating. And in an emergency, patients don’t have the luxury of time for research. Without any kind of regulation or oversight, it’s fertile ground for the opportunistic and unscrupulous.

What if we had told the surgeon, as I was about to be wheeled off, we thought his fee was too high? What would have happened?